A Dose of Hope

It’s been a tough year for ER doctors and nurses in the Philadelphia region. They’ve come a long way since those first terrible months.

Last spring, as bodies piled up in a refrigerated trailer outside Roxborough Memorial Hospital, emergency room nurse Harry Caramanica said the stress caused his hair to fall out. He became withdrawn. He’d wake at night and see the faces of dead patients, the ones he couldn’t save, drifting above his bed.

Caramanica likened the early days of COVID-19 to the unfolding of a horror movie:

“So you know there’s a monster. You can see the destruction that the monster causes, but you don’t really know what it is.

“Now that we know it a little bit better, we can spot it a little bit better, we’re all less terrified of it.”

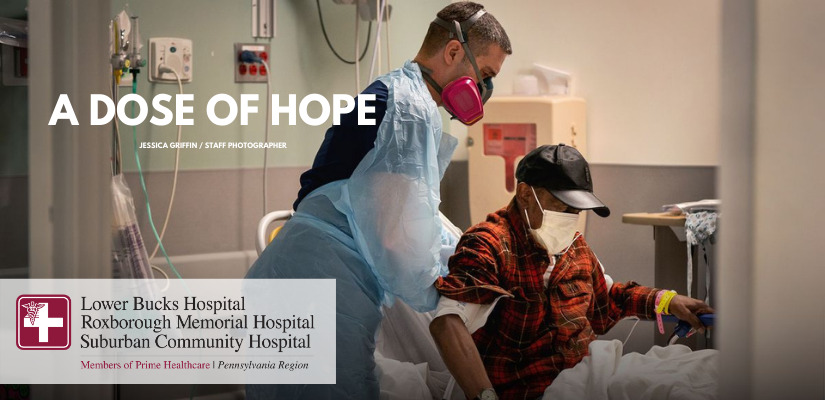

ER nurse Harry Caramanica prepares to give COVID-19 patient Herman Ebo oral medication and adjust the oxygen tubes beneath his nose at Roxborough Memorial Hospital in mid-January.

Now, nearly a year later, Philadelphia-area hospitals are still swamped with coronavirus patients, but they’re younger and less sick, and they don’t wait until it’s too late to go to the ER. Medical staff know better how to care for them. There are more treatment options, too, like monoclonal antibodies.

Caramanica’s hair has grown back. He’s more talkative at home, thanks to a low dose of antianxiety medication. Faces no longer haunt him at night. And better still, he’s fully vaccinated, as are roughly 300 of the 575 hospital staff. As one ER doctor at Suburban Community Hospital put it, in Star Trek terms, “Shields are up and activated.”

The Inquirer spent five days last month shadowing nurses and doctors at three local ERs — Roxborough in Philadelphia, Suburban in Montgomery County, and Lower Bucks Hospital in Bristol. Prime Healthcare, which runs all three community hospitals, invited reporters to gauge how battle-tested staffers are faring almost a year into the pandemic. They’ve run a marathon at a sprinter’s pace. While the finish line is not yet in sight, it feels within reach.

“So if we look at the journey, the journey is from uncertainty to some hope now,” said Dr. Mathew Mathew, chief medical officer at Suburban Hospital in Norristown. “We can see the evolution of the hope.”

‘I humbled myself’

Mathew’s COVID-19 journey began in early April when he got sick from one of his patients. While he knew about deadly outbreaks in Wuhan, China, and soon, Italy, he didn’t recognize his patient’s symptoms at first. The hospital wasn’t yet testing for the virus, Mathew said, and staff didn’t have adequate personal protective equipment.

“We didn’t know what was going on,” he said. “Also, for my part, probably, I didn’t take it seriously.”

The 65-year-old physician, who sports a silver goatee and dark-framed glasses, is high risk: He suffers from diabetes, high blood pressure, and heart disease. For five days he was hospitalized with COVID-19. His staff treated him. All around him, patients with similar medical conditions were dying. He was too sick to ponder his odds.

His fever spiked so high that he started hearing voices and seeing phantoms. He doesn’t remember what the ghosts said, only that they were noisy. “It was an experience,” he said, mildly. “Being on the other side as a patient, I humbled myself.”

Dr. Mathew Mathew, chief medical officer at Suburban Community Hospital in Norristown, looks through paperwork while on a recent conference call. Mathew, who got severely ill with COVID-19 in early April, spends a lot of time reviewing the medical histories of patients seeking an infusion of monoclonal antibodies. Not every patient qualifies for the COVID-19 treatment.

Mathew was a long hauler. Fatigue, memory loss, and anxiety lingered through summer. By then, COVID-19 cases had dropped here, but surged in India, where Mathew’s 94-year-old mother lives. (She hasn’t had COVID-19). In September, his native India was on track to overtake America as the country with the highest number of daily cases. But India’s cases quickly and dramatically declined, baffling scientists. Mathew said it’s no mystery. Americans, he believes, prize personal freedom over social responsibility.

“Here, we have individual rights,” he said. “Over there in India, police will come and put you in a place where you can’t get out if you violate quarantine rules.”

COVID-19 cases at Suburban Hospital jumped in December and early January, in part because of holiday gatherings from Thanksgiving through New Year’s. In the spring, one out of three of its patients tested positive. In mid-January, the rate was two in three. But the hospital’s death rate has plunged, Mathew said, from 35 to 40% last spring to roughly 3%.

“Will I see my grandkids grow up?”

Candi Selig, COVID-19 patient

In the early months, doctors cycled through treatments that probably didn’t work, Mathew said. The antimalaria drug hydroxychloroquine? “That went out of favor quickly.” An antiparasitic called Ivermectin? “That’s gone. We don’t use it anymore.” Rheumatoid arthritis medications? Also done.

It was like being on one of those Scrambler rides on the Jersey Shore boardwalk. A thrust forward, then a swift jerk back. Doctors finally came to a stop on a winning combo of remdesivir, an antiviral, and steroids for COVID-19 patients with low oxygen saturation. For less sick patients with high-risk conditions, an infusion of monoclonal antibodies.

Dr. Robert Selig, a pediatrician, is treated for COVID-19 in the ER at Suburban Community Hospital in Norristown. He rests on a hospital bed while getting an IV infusion of monoclonal antibodies to help fight the virus.

Suburban Hospital now has roughly 700 doses of two brands of the antibodies, the treatment, once in scarce supply, that former President Donald Trump got. On a single day in January, Mathew received seven calls from primary care doctors seeking antibodies for their patients, but scheduled only three of them for the next day. The outpatient treatment, administered by already taxed ER staff, is labor intensive. Not every patient’s medical condition qualifies them.

On Jan. 13 at about 8:30 a.m., Robert Selig and his wife, Candi, settled into an ER bay at Suburban for an hour-long IV infusion of antibodies. Both were sick with COVID-19. Selig, a 70-year-old pediatrician with diabetes and cardiac problems, broke out in a fit of coughs. He lay back in a hospital bed, eyes closed, his right hand resting on his electric-blue polo. Candi Selig, a pediatric nurse-practitioner, was beside him in her own bed, sluggish with fever, and pale as the crisp sheets. She touched her fingertips to her forehead. “I’ve had enough,” she said.

Pediatrician Robert Selig, 70, and his wife, Candi Selig, a pediatric nurse practitioner, await an IV infusion of monoclonal antibodies, a COVID-19 treatment once in short supply, while in the ER last month at Suburban Community Hospital. Within 48 hours of the infusion, Robert Selig said the couple felt much better and are now doing well.

Of 13 staff at their Philadelphia-based pediatric practice, five recently tested positive: Selig and his wife, two nurses and their office manager. “We had an outbreak,” Robert Selig said. “All of the sudden, the last couple of days, it’s a mess.”

For 10 months, they’d taken every precaution, installing special air-filtration in the office and swabbing kids for COVID-19 in the parking lot. Masks, face shields, gloves, routine staff screening — all a must. Selig holds little sympathy for parents who tell him that they can’t stop their teens from going out with friends. “The parents say, ‘I can’t control them,’ and I go, ‘Then, what you do is, you tell them if they are not going to wear a mask, you come back and you live in the garage for 10 days.’ ”

The pediatrician doesn’t know how they got COVID-19. The couple went to a grocery store five days before Candi spiked a 104-degree fever. “Could it be that?” he said. “We just don’t know.”

An ER nurse handed the Seligs extra blankets and pillows. Then she threaded an IV through their forearms. “You’re my brothers and sisters, period,” the nurse said, acknowledging them as frontline comrades.

Candi Selig didn’t want to go to the ER. It felt to her like a place of death. “Will I see my grandkids grow up?” she asked, teary-eyed.

Her husband was blunt. “What they are doing here is potentially saving one or both of our lives,” he said. “If you wait too long, then it’s too late.”

The vaccine’s gift

Upstairs on the third floor at Suburban, pharmacist Christine Gabos was squirreled away in a room no bigger than a bathroom stall. At 11 a.m., Gabos, with catlike hazel eyes framed by a hairnet of white gauze, stood at a counter, drawing vaccines from thumb-size vials into individual syringes. She’s been at it since before sunrise.

In an adjoining room, hospital staff signed in for their second doses of the Pfizer vaccine. Montgomery County health officials gave Suburban enough of the vaccine to immunize nearly 1,000 people, covering the hospital’s 475 staffers and local first-responders.

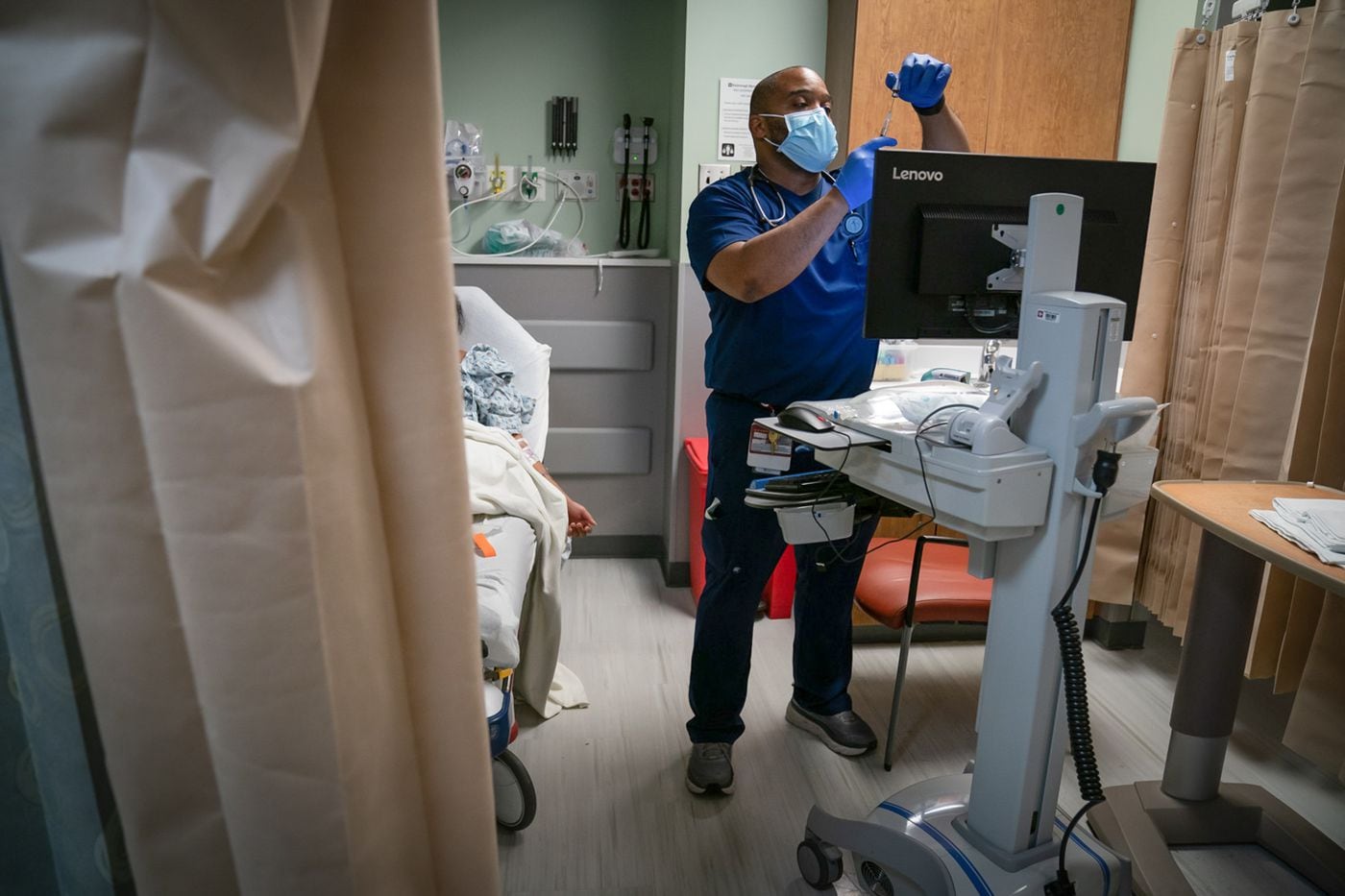

Pharmacist Christine Gabos prepares individual syringes of the COVID-19 vaccine at Suburban Community Hospital during a clinic for staff last month.

Laughter and chatter filled the room as medical workers rolled up their sleeves. Some took selfies. Jeffrey Heebner, a doctor affiliated with Suburban who specializes in geriatrics, marked the moment with a jubilant voice-to-text message to a friend: “I just got my second shot!”

Heebner said he can’t wait to stop worrying how to protect his patients at a nearby nursing home. Before COVID-19, the business of aging seemed straightforward. “Elderly people are realistic,” he said. “They want to get their pain controlled, they want to get a good night’s sleep and they want to have a good daily bowel movement.” He chuckled, then grew pensive.

“We’ve got to end this,” Heebner said. “And this is where it ends.”

Back downstairs, the ER was jumping. Both negative-pressure isolation rooms were occupied with COVID-19 patients. Posted outside each door was a large green “+” sign. Inside, one patient, barely visible through the glass, curled into an S-shape in a white-blanket cocoon. A third COVID-positive patient pressed his face against a glass-enclosed bay, signaling for a nurse.

A patient with COVID-19 is wheeled into an ER bay at Suburban Community Hospital in Norristown last month. A green “+” sign posted outside the door lets staff know which patients are positive.

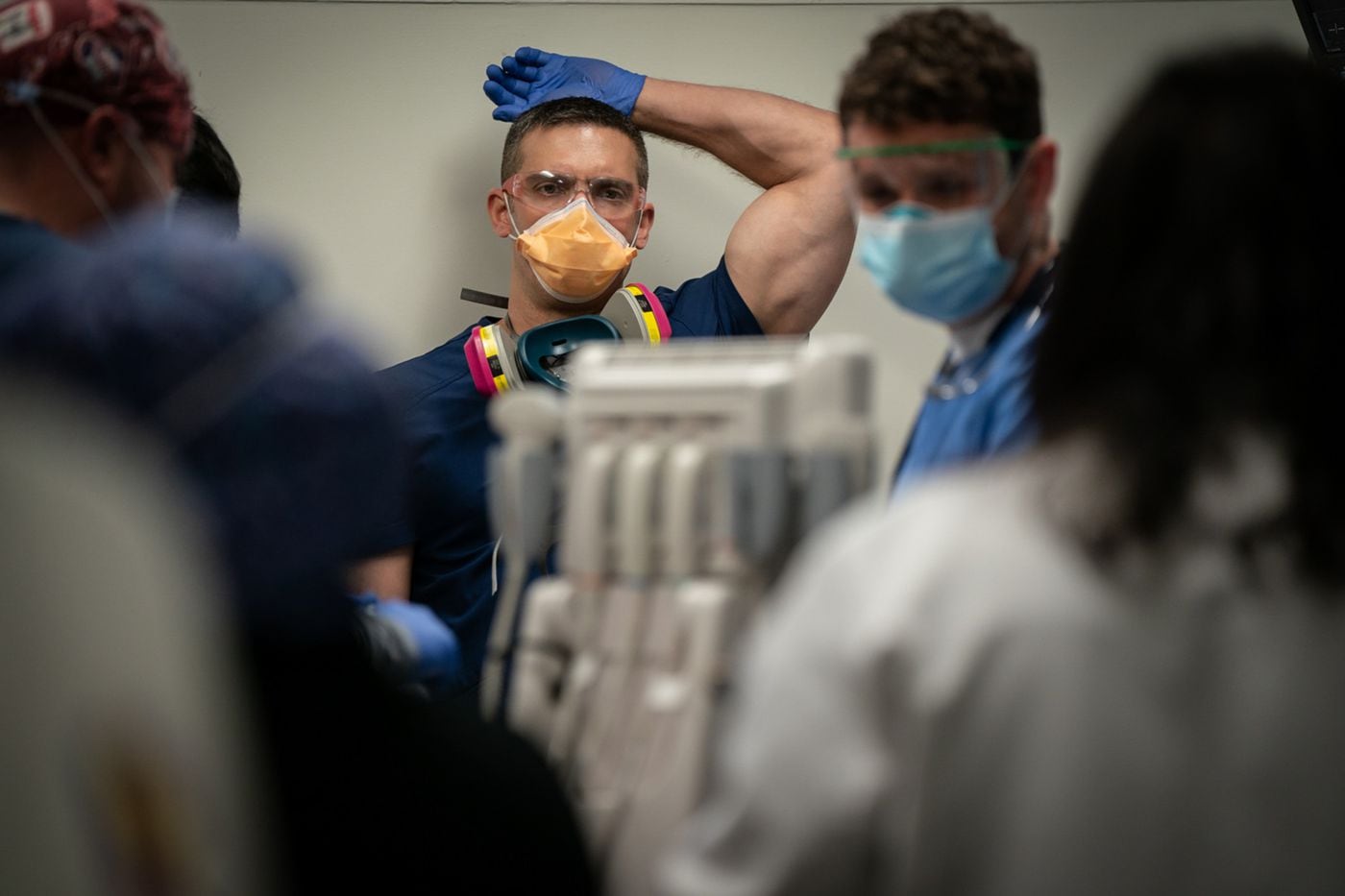

Just after 1 p.m., paramedics wheeled in a 71-year-old woman suffering cardiac arrest. Nurse Len Babula immediately started chest compressions. His only PPE was a paper surgical mask — a big change after months and months of donning near spacesuit-like gear. This is the gift of the vaccine: the ability to rush in and try to save someone without even thinking about COVID-19.

“We’re looking at 37 minutes now,” a paramedic yelled, marking how long it had been since they first tried to revive the patient.

Babula, in dark blue scrubs, pumped rhythmically, palms flat to her chest. On his bicep: a tattoo of a ship anchor and an American flag.

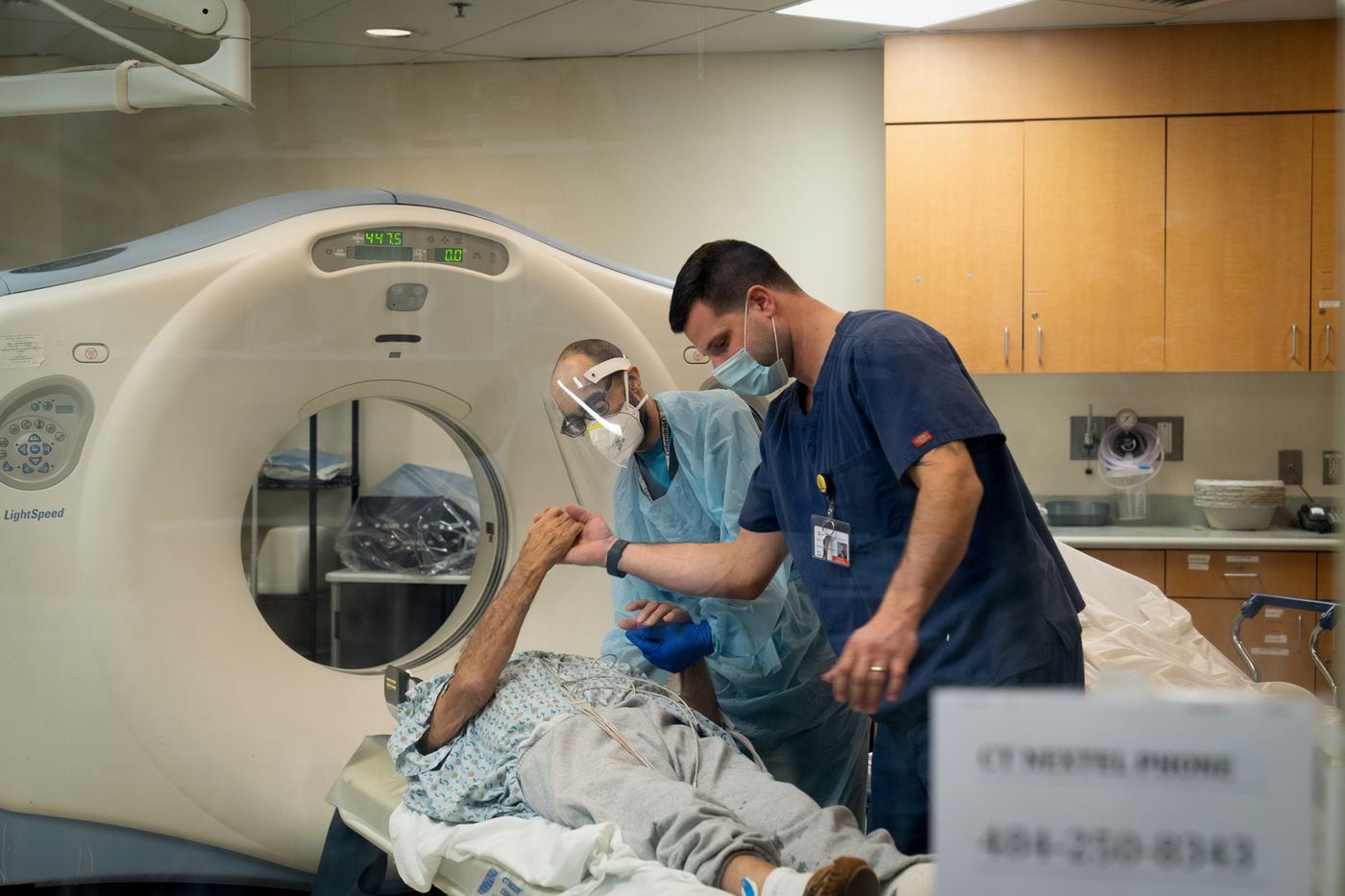

CT technologist Simon Jeffries (back, center) and ER nurse Len Babula (front) perform a CT scan on a COVID-19 patient at Suburban Community Hospital in mid-January. The patient is being treated for a persistent cough.

The 35-year-old nurse did two U.S. Navy tours in the North Arabian Gulf. “Special forces,” he said. “My job was to kind of not keep people so healthy. That takes a toll on you — morally.” While in the service, Babula took a tactical anatomy class where he learned how to use the enemy’s own body against him. When he came home, he went to nursing school where he learned to help people make their bodies work for them.

“I got nothing,” Babula shouted above a mechanical whine as the electrocardiogram traced a flat line.

“I’m gonna call it,” said ER doctor James McHugh.

A nurse pulled a blanket up, tucking it just below the woman’s chin, as if putting her to bed.

Moments later, Babula and McHugh tore down the hall to a trauma room, where a 68-year-old man was coding, his face purple.

McHugh, wearing a flimsy plastic face shield and a lavender disposable mask, inserted a breathing tube into the man’s throat as he thrashed on a gurney. Babula, along with a nurse, Cyndy Martinez, held him still and gave him a sedative.

Hospital ER staff intubate a critically ill patient last month at Suburban Community Hospital in Norristown. After helping to stabilize the man’s oxygen levels and heart rate, nurse Cyndy Martinez expresses relief: “I don’t know how he’s going to do tomorrow, but he didn’t die today.” He did not have COVID-19.

McHugh emerged from the room. The floor behind him was smudged with blood and strewed with latex gloves, syringe wrappers, and empty IV-fluid bags. McHugh suspected the man suffered a pulmonary embolism and did not have COVID-19, though he was not entirely sure. Like Babula, the 63-year-old doctor was recently vaccinated.

“You still have to be careful,” McHugh said, “but we’re lessening our guard a little bit.”

The ER staff learned months ago that they risked dangerous exposure while intubating patients. McHugh thought back to the pandemic’s beginning, when scientists surmised that the COVID-19 virus was “such a heavy molecule that when it came out, it hit the floor, like little metal balls.”

“It just didn’t make sense to me.”

Cyndy Martinez, an ER nurse at Suburban Hospital, cleans up the floor inside the trauma room after the staff intubated and stabilized a critically ill patient. Martinez said she wanted to safely dispose of potential biohazards to help protect the hospital’s cleaning staff.

One saving grace

Drug and alcohol abuse cases are on the rise at Suburban and other area ERs. When isolated, people self-medicate.

“Everybody is upset and depressed and they’re turning to their vices,” ER technician Theresa Wirtshaster noted, wearing plum-colored scrubs.

Next door to the room with the intubated male patient, a woman sobbed uncontrollably. “I’m leaving!” she announced. “It’s my right to leave.”

Rasheeda Smith, the hospital’s security officer, tried to calm her: “You want more soda?”

“I need air in here!” the woman screamed.

“If you calm down, I’ll leave the door open,” Smith responded. “Listen. Listen. I’m gonna leave it open, but you gotta stop yelling, OK?”

Rasheeda Smith, a security officer at Suburban Community Hospital, commutes to work from her West Philadelphia home, where she lives with her wife and their 14-year-old son. Smith maintains a soothing and upbeat bedside manner with agitated patients suffering from drug addiction. Her wife took care of her when she got COVID-19 in November, she says.

A few minutes later, Smith, who is short and stocky with girlish braids, returned with a white Styrofoam container of tilapia, string beans, mac and cheese. Two miniature candy canes sat on top. “Something to make her feel very special,” Smith said after handing her the meal.

“She’s coming down from whatever she’s coming down from,” Smith said. “We want to hold her to make sure she’s OK because we can’t release her like that.”

It’s been some year. Even Smith has felt it.

Smith, 32, who commutes to the hospital from her West Philadelphia home, had COVID-19 in November. Her 14-year-old son felt isolated from his friends and frustrated by remote learning. “He was so overwhelmed,” she said. “I’d be lying if I said I understand. I never had to be home all day learning on a computer.”

Nurse Sherry Seymour gestures to a colleague to request supplies while treating a COVID-19 patient inside a glass-enclosed ER bay at Suburban Community Hospital.

The next afternoon, nurse Sherry Seymour tended to a 60-year-old woman who’d overdosed on fentanyl. Paramedics found a small bag of crystal meth secreted in her bra. Seymour recognized the patient’s name. She’d treated her the day after Christmas. Seymour pulled up her chart. The computer screen scrolled and scrolled. At least eight separate ER visits in recent months: Hemorrhagic stroke. Systolic. Diastolic heart failure. Opioid drug overdose. Change in mental status.

Seymour, 51, has worked at Suburban for 22 years — eight in the ER. Long enough to know what to ask the woman. “You OK at home? You safe at home? You sure? Boyfriend situation? You know who to call for help?”

Earlier, Seymour had lamented that friends and relatives aren’t allowed to sit with patients in the ER because of COVID-19. Now, she’s glad for it. For victims of domestic violence or sex trafficking, the no-visitor rule is perhaps the pandemic’s only saving grace.

“Say she did have a pimp. If he’d be sitting there, she wouldn’t say a word,” Seymour said. “Just me and her? It’s just, ‘Look into these big blue eyes and tell me what’s going on.’”

A staff person walks past a display of stars, each one representing a patient who tested positive for COVID-19 and was discharged from Suburban Community Hospital.

A ticket to hell

During the first wave of COVID-19, Lower Bucks Hospital wasn’t hit as hard as Suburban in Montgomery or Roxborough Hospital in Philadelphia. Bucks County residents live farther apart and community spread was slower, said Dr. Ronak Bhimani, chief medical officer at Lower Bucks.

That changed in December and early last month. Twin scourges slammed the 155-bed hospital: COVID-19 and psychiatric cases. “Humans,” Bhimani observed, “are meant to socialize.”

“I wish we could spray it in the air.”

April Martin, ER nurse, said of the COVID-19 vaccine

Bhimani got married just before the pandemic. He’s gone out with his wife just once since then — to a restaurant in Jersey. It’s just the two of them at home, and their mini-Goldendoodle Austin, in a townhouse in Fishtown. COVID fatigue, he gets it.

Last spring, patients with garden-variety maladies feared COVID-19 and stayed away from the ER. Now, some come in just for the company, like a patient who has suffered from leg pain for the past seven months. Asked “why today,” the patient told nurse April Martin, “I just wanted to get out of the house.”

Martin, who is 40, has three kids — 13, 12, and 3. She doesn’t let them hang with friends. That’s been hardest on her teenage daughter. Her youngest doesn’t remember a time before COVID-19. The nurse said, “He thinks it’s normal.”

April Martin, an ER nurse at Lower Bucks Hospital in Bristol, fastens a protective face shield just before entering an isolation room to check on a COVID-19 patient in late January.

She got her first vaccine shot on Dec. 17. It boosted her hope. She is one of 15 ER nurses who’ve signed up to help vaccinate Bucks County residents sometime soon. “I wish we could spray it in the air,” she said, laughing.

A leopard-print bonnet covered her blond hair. She wore a mask with cartoonish hearts and a red pin in the shape of a movie ticket that read, “Hell. Admit One.” She called patients “sweetie” or “hon.”

On a gray Monday morning in late January, six of the 12 patients in the ER were there in mental-health crises.

Zachary Michael Stapleford, a 25-year-old patient, checked himself in two days before. “I was having some suicidal thoughts,” he said.

He also tested positive for COVID-19.

For 62 hours and 36 seconds he’d been stuck in an ER isolation room. The staff couldn’t move him to a bed upstairs in the hospital’s psychiatric unit until he tested negative. At all three hospitals, ERs became de facto psychiatric wards during the pandemic.

There’s only one mental health facility in the area that takes psychiatric patients with COVID-19. It’s always full, so patients sit in the ER for days.

Some patients get agitated. They hit, scratch, and bite nurses. Over the summer, one patient knocked Martin’s protective eyewear askew and spat in her eye. “Luckily she wasn’t positive for COVID, but I was a mess all day.”

Stapleford had a slight cough when he came in, but was more sick from despair.

“I don’t feel worthy of what I want in life,” Stapleford said. “I’m just trying to get the help I need to survive.”

“We’re grateful for that,” Martin reassured him.

Being alone in this room hasn’t been all bad. It’s given him time to reflect and heal, Stapleford said.

“To be honest, I just feel ready to change,” he said. “Once I get this mental health treatment and get over COVID, I feel like I’ll be able to take life head on.”

‘I’m still mad at it’

Herman Ebo coughed, then moaned, and coughed again. Each time, his feet jerked upward from the hospital gurney. Moving felt like a punch to the gut.

“Oh. Boy. Ugh,” he groaned, his surgical face mask puffing. “This goddamn cough is killing me.”

COVID-19 patient Herman Ebo, a 72-year-old retired U.S. Post Office clerk, puts his hand up to his face as he tries to control a bad cough while in the ER last month at Roxborough Memorial Hospital in Philadelphia.

Two days earlier, the 72-year-old military veteran had tested positive for COVID-19. On this January afternoon, he was in Roxborough’s ER. Harry Caramanica, the nurse, placed his latex-gloved hands under Ebo’s armpits and gently lifted him higher in the bed.

Their faces were close, about a foot apart. Caramanica, who sports a crew cut that does little to hide the bald patches where his hair fell out, wore a light blue disposable gown over his scrubs and a half-face respirator, but no protective goggles. When he realized he’d forgotten them, Caramanica shrugged. It’s a slip up that would’ve unnerved him only a month ago. But he’s vaccinated.

“Are you having trouble getting air?” Caramanica asked Ebo.

Caramanica looped a clear plastic tube around Ebo’s ears, positioning the U-shaped tube under his nostrils. “I’m going to put you on a little oxygen,” he told him.

In the earlier days of COVID-19, ER nurses and doctors quickly intubated patients who struggled to breathe; they bemoaned a shortage of ventilators. They’ve since learned that intubation is bad for the patients. Forcing air into ravaged lungs didn’t distribute oxygen to the bloodstream, it just exhausted them until they quit.

“The best thing that happened was they told us to stop intubating people right away — that saved a lot of lives,” Caramanica said.

“Black people — we just died from it more than anybody. It’s been so hard.”

Charlotte Avery, patient

Ebo is at great risk. He’s on dialysis for bad kidneys. He recently had a bowel obstruction that required surgery. Half of last year he was hospitalized with pancreatitis. After a course of steroids and antibiotics, he was discharged from Roxborough two days later. During a phone call with a reporter, he talked about plans to take “a lady friend” out to dinner for her 65th birthday. “Someplace nice,” he said.

Roxborough is a community hospital in the truest sense. On the morning of January 18, paramedics burst through the ER doors with a 37-year-old man with no heart beat. The whole staff knew him. He suffered from spina bifida, a condition that brought him to the ER many times. When he died, a doctor cried in a corner.

ER Nurse Harry Caramanica treats patient Charlotte Avery for chest pain at Roxborough Memorial Hospital in Philadelphia. The 69-year-old Roxborough woman says COVID-19 took the lives of 25 relatives and friends. Protective of her health, Avery’s grown children and grandchildren haven’t hugged her since April.

Caramanica, 44, lives a few blocks from the hospital. A 69-year-old woman he knew both from her ER visits and his neighborhood arrived with chest pain.

“Miss Avery! Hi!” Caramanica greeted her, striding over in his neon orange Pumas.

“Hi everybody,” Charlotte Avery called out.

“Your asthma bad again?”

“Not the asthma so much. Just chest pain.”

COVID-19 has rocked Roxborough.

Avery has 30 friends and relatives who got the virus. Of them, 25 died. “I’m still mad at it,” she said, tearing up. “Black people — we just died from it more than anybody. It’s been so hard.”

Nurse Micah Maxton lost his aunt and cousin to the virus, and too many friends and acquaintances. The 47-year-old from North Philadelphia started his career in the ICU at Einstein Medical Center, then took a job in the trauma unit at Temple University Hospital because he wanted to help his community, he said. He left there, taking a job at Roxborough, after a nightmarish summer about 12 years ago. During a single shift, 17 gunshot victims came in. Eleven, each Black, died. One victim was a friend’s 19-year-old daughter struck by a stray bullet while walking into her house.

But COVID-19, he said, hit far worse.

ER nurse Micah Maxton treats a patient with a severe migraine at Roxborough Memorial Hospital in Philadelphia last month. Maxton, who grew up in North Philadelphia, lost an aunt, cousin and scores of friends and acquaintances to COVID-19.

“I’ve never in my life experienced so many deaths in such a short time. Ever,” Maxton said. “Patient after patient after patient — tubing, intubating, proning. Meanwhile, you are trying to keep safe.”

“It absolutely changed me,” he added. “I’m more cognizant of little things … Just appreciating life.”

He sipped a hot caramel coffee from Dunkin’ Donuts. Pure joy.

The hospital sits across from rowhouses with covered stoops where neighbors like to gather and talk. At the height of the pandemic, Sean McDonald, an ER technician, had to transport the bagged bodies from the hospital’s tiny morgue to a refrigerated truck in the parking lot. He did it in the middle of night so the neighbors wouldn’t see. One warm May night, a bag broke open, revealing the body of a man in his 60s.

“I got home and I lost it that night,” McDonald recalled. “It made me question if this is what I wanted to do with my life.”

Sean McDonald, an ER technician, covers a patient who passed away from health issues unrelated to COVID-19 at Roxborough Memorial Hospital in Philadelphia. The 35-year-old from Elkins Park plans to become a nurse.

On Jan. 19, his 35th birthday, he was working a 10-to-6 p.m. shift because he has a night class to get his medic certification. He plans to go to nursing school. Roughly 90 minutes into his shift, two patients died within seconds of one another. After performing chest compressions on a 61-year-old patient without success, McDonald spotted a rosary among the sheets. He laid it on the man’s chest.

“I’m gonna cover him up. Let him go in peace,” McDonald said to Caramanica.

McDonald shook his head and sighed. “Happy birthday to me.”

“It’s still better than March, right?” Caramanica said.

“I won’t say it’s better,” McDonald replied. “It’s different.”

Roxborough had only one COVID-19 patient on a ventilator — a marked improvement. The medical staff has come to realize that lockdowns work to reduce COVID-19 cases. Two weeks ago, 50% of the patients who came to the ER had the virus. Today, it’s below 10%.

Caramanica noted that Philadelphia had just relaxed social distancing restrictions again, “So we’ll see how it goes.”

Nurse Harry Caramanica reacts after a patient, who was well-known and well-liked by ER staff at Roxborough Memorial Hospital, passes away shortly after Caramanica performed chest compressions in an effort to save the patient’s life.

Patrick Lenahen, Roxborough’s chief medical officer, said just one or two hospital staffers got COVID-19 in the spring, but last month, at least 16 were either out sick or in quarantine after an exposure. “It’s curious,” he said, wondering if a new, more contagious variant is to blame. Or maybe, COVID-fatigued staff gathered with family over the holidays?

Unlike at Suburban and Lower Bucks, where county health officials gave each hospital hundreds of vaccines all at once, Philadelphia’s Health Department provides Roxborough with only 100 doses a week, he said.

“To wait six more weeks to get all 600 doses is not the end of the world, but it’s hard for people who are anxious to have it and to be told, ‘Sit tight, we’ll get to you,’” Lenahen said.

The 67-year-old doctor, who has a full head of snow white hair and hip, chunky eyeglass frames, is the lead singer in a band called The Providers. He’s looking forward to playing gigs again, he said.

Caramanica is worn out, and yearns to spend more time with his wife and 5-year-old son. He fantasizes about a mandatory stay-at-home order just for hospital staff once the region reaches 80% herd immunity.

“Maybe they can give us a lockdown,” he said, laughing. “Just lock us all down.”

Harry Caramanica, an ER nurse at Roxborough Memorial Hospital, rubs his forehead in dismay after a patient passes away. Standing next to Caramanica, ER technician Sean McDonald shares a solemn moment.